Still rocking my khakis with a cuff and a crease

I’m young enough that my musical tastes, such as they are, really developed in the Age of Napster. Sure, I had one or two tapes and a few dozen CDs, but I really became a fully-formed listener by downloading songs one at a time.

As a result, I’m generally disinterested in the full album experience. I prefer a mix tape over an EP.

However, one of the few exceptions is Dr. Dre’s classic The Chronic: 2001.

Released in 1999, this album was heralded by the hit single “Still D.R.E.” which proudly proclaimed that the former producer of N.W.A. was back and hungry to prove that he was still the best.

A follow-up to 1992’s The Chronic, 2001 has a similar format to its predecessor. All the beats are composed by Dre, with a host of guest appearances from his stable of rapping protégés and occasional appearances by the man himself.

Dre pulled together an impressive roster of friends for this opus: West Coast rap stalwarts Snoop Dogg and Nate Dogg return, along with former N.W.A. member MC Ren. The Chronic: 2001 also introduces younger rappers headlined by Xzibit and Eminem.

“Still D.R.E.” and “Forgot about Dre”, the second single from the album, are indicative of the album’s main theme about the good Doctor’s status in the music industry.

Like the rest of the album, he’s trying to reconcile his reputation, his violent image from a decade ago and the reality of being a multi-millionaire who no longer lives on the infamous streets of Compton, California on these tracks.

As Dre said himself in an interview with the New York Times:

“For the last couple of years, there's been a lot of talk out on the streets about whether or not I can still hold my own, whether or not I'm still good at producing,” he said just before 2001 was released. “That was the ultimate motivation for me. Magazines, word of mouth and rap tabloids were saying I didn't have it any more.”

“What more do I need to do? How many platinum records have I made? O.K., here's the album -- now what do you have to say?”

In the same interview he explains how he saw the unfolding of the album to be like a movie following a plotline.

That story arch is apparent from the very first track “Lolo” when Xzibit and Tray-Dee are shocked to see Dr. Dre appear at a local hangout in a brand new lowered car.

The second track is a soliloquy by Dre called “the Watcher” about all the things he’s seen in his career. The next four tracks follow a similar subject, with Dre and some of his older associates reminding the listener of their past exploits and successes.

“What’s the Difference” serves as a turning point in the album, as rookies Xzibit and Eminem take up Dre’s cause and talk about how he’s shaped their careers.

Once he’s re-established himself as a force in the music industry again, the rest of the album talks about moving forward (“The Next Episode”) and revelling in all of Dre’s new success.

No one can doubt Dr. Dre’s chops as a producer. He’s proven himself time and time again. But the Chronic: 2001 should be admired not just for its music but the clever way he uses lyrics and guest appearances to express his frustration with all of the premature claims of his decease as a viable music artist.

It’s a creative use of rap’s braggadocio lyrical style that can be enjoyed again and again.

Why I love rap music

I’m not a particularly musical person – I was kicked out of the school band in grade 7 because I was so inept at playing the trumpet – but I love listening to music.

In fact, whenever I write I have my iTunes running on random shuffle. Although I’ve got an eclectic collection of songs, the vast majority of it is hip-hop.

The reason is simple - even though I’m a middle class white guy, rap music speaks to me more than any other genre. Sure, I like rock, country or even some classical music but for me, nothing compares to urban music.

I’ll be the first to admit I come from a very different world than most rappers. Aside from Drake – who grew up around the corner from my apartment – I can’t honestly say that I identify with the hard, impoverished world of many rappers. The violent and often criminal reality of a rapper like Snoop Dogg or Dr. Dre is something I’ve never experienced and hope I’ll never have to.

However, I can identify with Dr. Dre’s concerns about aging and re-establishing his personal identity as he does in the classic album Chronic: 2001. I can also empathize with Jay-Z on his track Young Forever from the Blueprint III. The subject matter may be foreign, but the themes are universal.

Unlike a lot of media, rap often conveys narratives with humour and playfulness that belies the seriousness of the content. As the Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates recently pointed out, a talented MC like Ghostface Killah can make you laugh while describing selling drugs in a school zone.

I think a fair comparison would be enjoying classic literature. I will never be in the dense colonial jungles like Kurtz in Heart of Darkness and I will never be a drug dealer like the Notorious B.I.G. in “Juicy”, but I can be moved by both.

However, hip-hop makes itself more accessible then a lot of other media by being the most culturally aware of all musical genres.

Lyrics refer to historical events, other musicians, television, comic books or movies. You just can’t find a line like Everlast’s “Because I can feel it in the air tonight/but yo I’m not Phil Collins/I’m more like Henry Rollins” in other kinds of media. At least, not often.

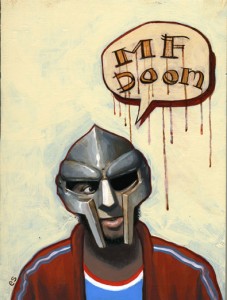

Whether it’s the Beastie Boys name-checking Star Trek, the various members of the Wu Tang Clan creating “secret identities” based off of super-heroes from Marvel Comics or MF Doom basing his entire persona of the villain of the same name, rappers locate themselves in a cultural context that any listener can easily identify.

It goes well beyond lyrical styling - the beat itself is often a sample from another song or a television show. Busta Rhymes using the theme from Knight Rider or DMX and Onyx using the intro to Welcome Back Kotter for “Slam Harder”.

The music itself is a clever nod to the urban environment that it’s created in.

Floating snippets of familiar hooks and beats and sampled choruses are reminiscent of music floating out of neighbourhood windows as you walk down the street. Thumping bass simulates the clacking of subway cars riding on aging tracks. Changing lyrical flow or rotating MCs is a lot like catching parts of a conversations as you pass people on the sidewalk.

It’s impossible to listen to Grand Master Flash and the Furious Five’s “the Message” and not recognize the frustrations of living in a city. The same can be said of Kurtis Blow and Run DMC’s collaboration for “8 Million Stories”.

This culturally-awareness is the great strength of rap. It makes it more relatable and current. These references helps hip-hop bridge significant divides like politics, gender, religion and, of course, race. Hip-hop inspires and entertains me like no other kind of music.