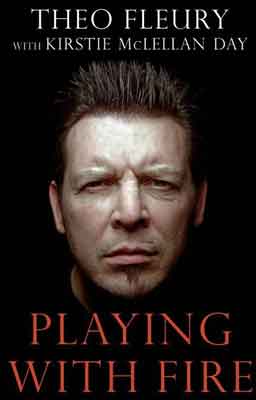

Book Review – Playing with Fire by Theo Fleury

Theo Fleury’s autobiography Playing with Fire is as direct and hard hitting as his play was on the ice.

Theo Fleury’s autobiography Playing with Fire is as direct and hard hitting as his play was on the ice.

That shouldn’t surprise anyone who followed the National Hockey League in the 1990s. Fleury was known as much for his energetic style and dynamic playing-making ability as his knack for pissing people off and getting in to trouble both in the arena and in real life.

Playing with Fire is Fleury’s memoir and confessional where he brings every imaginable skeleton out of his closet for all to see.

It’s a dark, often depressing look at his life on and off the ice. The turning point of the book comes early, when Fleury attends Andy Murray’s hockey camp and meets the scout and junior hockey coach Graham James, infamous for being convicted of the molestation of NHLer Sheldon Kennedy.

Of course, when the 13-year-old Fleury attended the camp, James’ dark second life wasn’t public knowledge and, according to the book, the vulnerable kid from Russel, Manitoba soon fell victim along with his friend Kennedy.

This revelation is what grabbed all the headlines when Playing with Fire was first published in 2009 and it is the central issue of the entire autobiography. All of Fleury’s behaviour afterwards is a reaction to the alleged abuse, either to distract himself from the guilt and pain of James’ assault or because he’s lashing out in anger.

Playing with Fire therefore serves as Fleury’s confessional, as he tries to explain his behaviour for most of his adult life and also tries to apologize to the many people he hurt or wronged, including teammates like Craig Conroy and Robyn Regher but especially his children Josh, Beaux and Tatym.

In many respects, reading Playing with Fire reminded me of professional wrestler Bret Hart’s autobiography Hitman. Both are athletes with deep connections to Alberta and Calgary, both are known for their incredible skills and both have a variety of personal problems stemming from abuses suffered while they were kids.

However, there are still differences. Hart is undoubtedly the better writer, but Fleury is the more genuine author. Hart is shockingly cavalier about the sex, drugs and violence in his professional and personal life, while Fleury is remorseful and regrets most of his behaviour.

Although this makes Playing with Fire less entertaining than Hitman, it’s also more emotionally fulfilling. The lows may be lower in Fleury’s narrative, but the highs are also higher.

Hart comes across as a bitter old man by the end of his book, while Fleury is clearly a happier, healthier person hoping to give back to society through his book, public speaking and charitable works.

Playing with Fire is definitely worth a read. Not just for hockey fans who want to read all about Theo Fleury’s wild stories, but for its value as a cautionary tale for any parents considering getting their child involved in amateur hockey.

Archives

- February 2014 (1)

- June 2012 (1)

- January 2012 (1)

- December 2011 (1)

- November 2011 (2)

- June 2011 (3)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (2)

- February 2011 (5)

- January 2011 (5)

- December 2010 (3)

- November 2010 (11)

- October 2010 (11)

- September 2010 (7)

- August 2010 (10)

- July 2010 (10)

- June 2010 (5)

- May 2010 (14)

- April 2010 (18)

- March 2010 (24)

- February 2010 (22)

- January 2010 (20)

Categories

- Books (18)

- Comics (15)

- Food (2)

- Movies (3)

- Music (2)

- Personal (4)

- Reading (22)

- Site administration (7)

- Sports (143)

- Television (2)

- Video Games (2)

- Writing (23)